More From Raphael Sperry:

In 2005, Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) launched a “Prison Design Boycott” on the grounds that prisons are inhumane environments. Raphael Sperry, its longtime leader, has recently begun to focus full-time on the matter with the aid of a prestigious Soros Justice Fellowship. On behalf of ADPSR, Sperry has recently launched a Change.org petition–asking the American Institute of Architects to amend its Code of Ethics & Professional Conduct to prohibit the design of spaces for torture and killing. Sperry spoke yesterday at Architecture for Humanity‘s Design Like You Give a Damn: LIVE event in San Francisco, and is the subject of a lengthy feature and profile by Karrie Jacobs in ARCHITECT Magazine. Both Jacobs’ profile and the petition itself are well worth a read. Source: Public Interest Design.org

In 2005, Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) launched a “Prison Design Boycott” on the grounds that prisons are inhumane environments. Raphael Sperry, its longtime leader, has recently begun to focus full-time on the matter with the aid of a prestigious Soros Justice Fellowship. On behalf of ADPSR, Sperry has recently launched a Change.org petition–asking the American Institute of Architects to amend its Code of Ethics & Professional Conduct to prohibit the design of spaces for torture and killing. Sperry spoke yesterday at Architecture for Humanity‘s Design Like You Give a Damn: LIVE event in San Francisco, and is the subject of a lengthy feature and profile by Karrie Jacobs in ARCHITECT Magazine. Both Jacobs’ profile and the petition itself are well worth a read. Source: Public Interest Design.org

One October afternoon in downtown Toronto, a small band of protestors clustered outside the Hilton holding handmade signs with slogans like “Food not Prisons” and “Housing not Prisons.” The so-called Prison Moratorium Action Coalition was denouncing a sprawling piece of legislation passed in Canada’s Parliament earlier this year, one that imposed mandatory minimum sentences for many offenses and authorized a multibillion-dollar program for prison construction.

The target of this demonstration, however, wasn’t government officials or law enforcement agencies. Instead, it was the annual fall meeting of the Academy of Architecture for Justice. The protestors had decided to go after “others who profit from locking people away.” In this case, the “others” were architects—specifically, the Toronto-based Zeidler Partnership, including senior partner Alan Munn and several of his colleagues—who were at the Hilton presenting their newly completed maximum security Toronto South Detention Centre.

Munn, for his part, argues that the “ragtag group” was off-base in its efforts because Toronto South had nothing to do with the federal crime initiative. Rather, the crisply modern facility with its Miesian entry pavilion was the solution to a provincial problem, a replacement for older Toronto prisons, one of which dated back to 1858. “It’s really a response to some terrible conditions in existing facilities,” Munn insists.

Rightly or wrongly, it seems almost unprecedented to hold architects accountable for decisions that are political in nature. Normally, the only dissent heard at AIA events comes from the architects themselves.

In fact, deep inside the Hilton, the protestors had an ally. On the agenda was a panel called “Long-Term Solitary Confinement in the U.S.: Design and Implications.” One of the panelists, Raphael Sperry, a 38-year-old Berkeley, Calif.–based architect, has dedicated the past 10 years of his life to persuading his colleagues to stop designing prisons. Currently, he has a grant from the Open Society Foundations, a nonprofit founded by George Soros, to focus on his mission—the first architect selected as one of that organization’s Justice Fellows.

The points he made that day in October were simple: “Long-term solitary confinement is torture. Execution chambers kill people. Architects should not be party to torture and killing.” He then announced his campaign to amend the AIA’s Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct to “prohibit the design of spaces intended for long-term solitary isolation and execution.”

At first glance, the idea that the AIA would take a stand on incarceration practices or capital punishment seems counterintuitive, the issue too far removed from the organization’s mission. But Sperry framed his argument using the existing language of the code, pointing out that Ethical Standard 1.4 says that “members should uphold human rights in all their professional endeavors.”

“The Jailing-ist Country on the Planet”

In truth, what Sperry is proposing is the outgrowth of the debate that has long been an undercurrent of the profession: Do architects have an obligation to improve the human condition? From the Bauhaus’s promise of cheaper, better dwellings for all, to the current generation of do-gooder architects designing emergency shelters and affordable housing, the profession’s humanitarian impulse is never far from the surface. On the other hand, we can all name architect-designed buildings that have been portrayed as cruel in ways big and small. Minoru Yamasaki’s Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis comes to mind. As does Philip Johnson’s Bobst Library at New York University with its vast, vertigo inducing atrium that seemingly acted as an inducement to three recent student suicides. Not to mention that architects routinely act as enablers and promoters of the worst excesses of commercial development.

Arguably, the watershed moments in prison design have generally been more philosophical than architectural in nature. In 1776, the Philadelphia Quakers introduced the idea of solitary confinement at the Walnut Street Jail, to give prisoners ample time to reflect. And in 1787, philosopher Jeremy Bentham proposed the penitentiary panopticon, with a circular layout that placed an unseen jailer at the core of the building, giving him “invisible omniscience” as he watched over 1,000 prisoners. (Continue Reading Here)

Source: Architects Magazine

Follow Raphael on Twitter or FaceBook

_________________________________________________________________________________More About Juan E. Méndez: In 1970, he received his law degree from Stella Maris University in Mar del Plata, Argentina.

Early in his career, he became involved in representing political prisoners. As a result, he was arrested by the Argentinean military dictatorship and subjected to torture and administrative detention for 18 months. During this period, Amnesty International adopted him as a “Prisoner of Conscience,” and in 1977, he was expelled from the country and moved to the United States.

Subsequently, Mendez worked for the Catholic Church in Aurora, Illinois, protecting the rights of migrant workers. In 1978 he joined the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights under the Law in Washington, D.C., and in 1982, he launched Human Rights Watch’s (HRW) Americas Program. He continued to work at HRW for 15 years, becoming their general counsel in 1994.He is also a visiting scholar at American University Washington College of Law's Academy on Human Rights and Humanitarian Law.

From 1996 to 1999, Mendez served as the Executive Director of the Inter-American Institute of Costa Rica. He then worked as a Professor of Law and Director of the Center for Civil and Human Rights at the University of Notre Dame from October 1999 to 2004.

In 2001, Mendez began working for the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ), an international human rights NGO. He served as its president from 2004 to 2009, and currently is its President Emeritus. He is also currently the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture.

Mendez has taught human rights law at Georgetown Law School, the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, and the University of Oxford Masters Program in International Human Rights Law in the UK.

He has received numerous awards for his work, including the Goler T. Butcher Medal from the American Society of International Law; a Doctorate Honoris Causa from the Université du Québec à Montréal (University of Quebec in Montreal); the “Monsignor Oscar A. Romero Award for Leadership in Service to Human Rights” by the University of Dayton; and the “Jeanne and Joseph Sullivan Award” of the Heartland Alliance.

Source: Wikipedia.org

_________________________________________________________________________________

In 1970, he received his law degree from Stella Maris University in Mar del Plata, Argentina.

Early in his career, he became involved in representing political prisoners. As a result, he was arrested by the Argentinean military dictatorship and subjected to torture and administrative detention for 18 months. During this period, Amnesty International adopted him as a “Prisoner of Conscience,” and in 1977, he was expelled from the country and moved to the United States.

Subsequently, Mendez worked for the Catholic Church in Aurora, Illinois, protecting the rights of migrant workers. In 1978 he joined the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights under the Law in Washington, D.C., and in 1982, he launched Human Rights Watch’s (HRW) Americas Program. He continued to work at HRW for 15 years, becoming their general counsel in 1994.He is also a visiting scholar at American University Washington College of Law's Academy on Human Rights and Humanitarian Law.

From 1996 to 1999, Mendez served as the Executive Director of the Inter-American Institute of Costa Rica. He then worked as a Professor of Law and Director of the Center for Civil and Human Rights at the University of Notre Dame from October 1999 to 2004.

In 2001, Mendez began working for the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ), an international human rights NGO. He served as its president from 2004 to 2009, and currently is its President Emeritus. He is also currently the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture.

Mendez has taught human rights law at Georgetown Law School, the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, and the University of Oxford Masters Program in International Human Rights Law in the UK.

He has received numerous awards for his work, including the Goler T. Butcher Medal from the American Society of International Law; a Doctorate Honoris Causa from the Université du Québec à Montréal (University of Quebec in Montreal); the “Monsignor Oscar A. Romero Award for Leadership in Service to Human Rights” by the University of Dayton; and the “Jeanne and Joseph Sullivan Award” of the Heartland Alliance.

Source: Wikipedia.org

_________________________________________________________________________________Lawyers have an ethics code. Journalists have an ethics code. Architects do, too. According to Ethical Standard 1.4 of the American Institute of Architects (AIA):

“Members should uphold human rights in all their professional endeavors.”

A group called Architects, Designers, and Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) has taken the stance that there are some buildings that just should not have been built. Buildings that, by design, violate standards of human rights.

Specifically, this refers to prisons with execution chambers, or prisons that are designed keep people in long-term isolation (or as prison officials call it, “segregation”). The latter kind of prison is called a “supermax,” or “security housing unit” (SHU). There is no legal definition for solitary confinement, so it’s up for debate as to whether the SHU constitutes solitary confinement.

There has been a lot of controversy surrounding one SHU at a Northern California prison called Pelican Bay.

(Credit: California Department of Corrections)

Pelican Bay State Prison was designed by San Francisco-based architecture firm KMD. KMD declined to speak with us for this story. But Jim Mueller, an architect with KMD who worked on Pelican Bay, told Architect Magazine: ”“The inmates have no contact with other inmates during the vast majority, if not all, of the day. They are only allowed out of their cells for very short periods of time for constitutionally required exercise periods.”

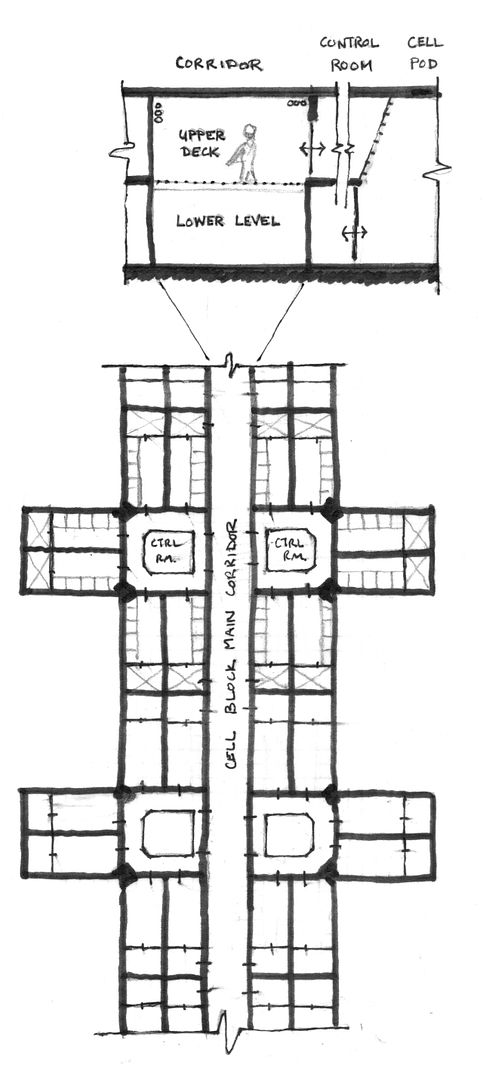

(Rendering of the Pelican Bay SHU. Each “pod” contains six cells, a shower, and an exercise yard. Control rooms monitor the pods, and can open and close cell doors remotely. The control rooms are accessed by an upper deck, which has a metal mesh floor allowing officers to fire a shotgun down into the pod in the event of a security breach. Courtesy of Raphael Sperry.)

Life inside of the SHU at Pelican Bay means 22 to 23 hours a day inside of 7.5 by 12 foot room. It’s not a space that’s designed to keep you comfortable. But it’s not just these architectural features, that concern humanitarian activists and psychiatrists. It’s the amount of time many prisoners spend in that cells, alone, without any meaningful activity. Some psychiatrists, such as Terry Kupers, say there is a whole litany of effects that a SHU can have on a person: massive anxiety, paranoia, depression, concentration and memory problems, and loss of ability to control one’s anger (which can get a prisoner in trouble and lengthen the SHU sentence). In California, SHU inmates are 33 times more likely to commit suicide than other prisoners incarcerated elsewhere in the state. There are even reports of eye damage due to the restriction on distance viewing. Terry Kupers says that a SHU ”destroys people as human beings.”

(Rendering of the Pelican Bay SHU. Each “pod” contains six cells, a shower, and an exercise yard. Control rooms monitor the pods, and can open and close cell doors remotely. The control rooms are accessed by an upper deck, which has a metal mesh floor allowing officers to fire a shotgun down into the pod in the event of a security breach. Courtesy of Raphael Sperry.)

Life inside of the SHU at Pelican Bay means 22 to 23 hours a day inside of 7.5 by 12 foot room. It’s not a space that’s designed to keep you comfortable. But it’s not just these architectural features, that concern humanitarian activists and psychiatrists. It’s the amount of time many prisoners spend in that cells, alone, without any meaningful activity. Some psychiatrists, such as Terry Kupers, say there is a whole litany of effects that a SHU can have on a person: massive anxiety, paranoia, depression, concentration and memory problems, and loss of ability to control one’s anger (which can get a prisoner in trouble and lengthen the SHU sentence). In California, SHU inmates are 33 times more likely to commit suicide than other prisoners incarcerated elsewhere in the state. There are even reports of eye damage due to the restriction on distance viewing. Terry Kupers says that a SHU ”destroys people as human beings.”

(Terry Kupers at the Conference on Solitary Confinement and Human Rights, November 2012.)

So if it is the ethical code of architects to promote human rights…what is their responsibility to the people who are incarcerated in their buildings?

Compared with some other prisons in the California system, the Pelican Bay SHU has some redeeming architectural features. Inmates can get natural light from skylights outside of their cells, which drifts in through doors made of a perforated metal. These porous doors also allow for inmates to communicate with each other, even though there are no lines of sight to any prisoner from within the cell.

(Prisoner Robert Luca sitting outside of his cell. Notice that the cell faces a blank wall, seen through the visual distortion of the perforated metal door. Credit: Nancy Mullane.)

But on the other hand, cells don’t have windows. Inmates never get to see the horizon. The only times prisoners get to leave the cell is to visit the shower, or the exercise yard—which is an empty, windowless room not that much bigger than a cell, with twenty-foot high concrete walls.

(KQED and the Center for Investigative Reporting launched an investigation on Pelican Bay in February, 2013)

Again, there is no universally accepted definition of solitary confinement. But some groups, like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have gone beyond calling the SHU solitary confinement—they call it torture. In 2011, the UN Special Rapporteur on torture said anything over 15 days in solitary confinement is a human rights abuse—which other sources have interpreted as torture.

Enter Raphael Sperry, a San Francisco-based architect and president of ADPSR. He believes it’s up to architects to lead the charge against these buildings. Sperry and the ADPSR are trying to get the American Institute of Architects to adopt an amendment to their ethics code:

“Members shall not design spaces intended for execution or for torture or other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, including prolonged solitary confinement.”

(Under surveillance in the exercise yard. Credit: Nancy Mullane)

This episode is a special collaboration between 99% Invisible and the podcast Life of the Law. 99% Invisible producer Sam Greenspan spoke with Raphael Sperry and Terry Kupers about the effects of these kinds of prisons on the people who inhabit them, and what they say about the practice of architecture as a whole in the US.

In addition, Life of the Law’s Nancy Mullane drove very, very far to visit the SHU at Pelican Bay State Prison, where she spoke with prisoners and prison officials about life in the SHU.

Source: 99% Invisible.org

Compiled By: Josh Martin

Please Support My Sponsors:

Source: 99% Invisible.org

Compiled By: Josh Martin

Please Support My Sponsors:

No comments:

Post a Comment